[:en]

Despite the fact that there are previous measurements, these used, in addition to observations, a theoretical model. For the first time, scientists of the Millennium Institute of Astrophysics MAS and the European Southern Observatory ESO carried out a fully empirical estimate of the total mass of the stars that are part of the Milky Way Bulge.

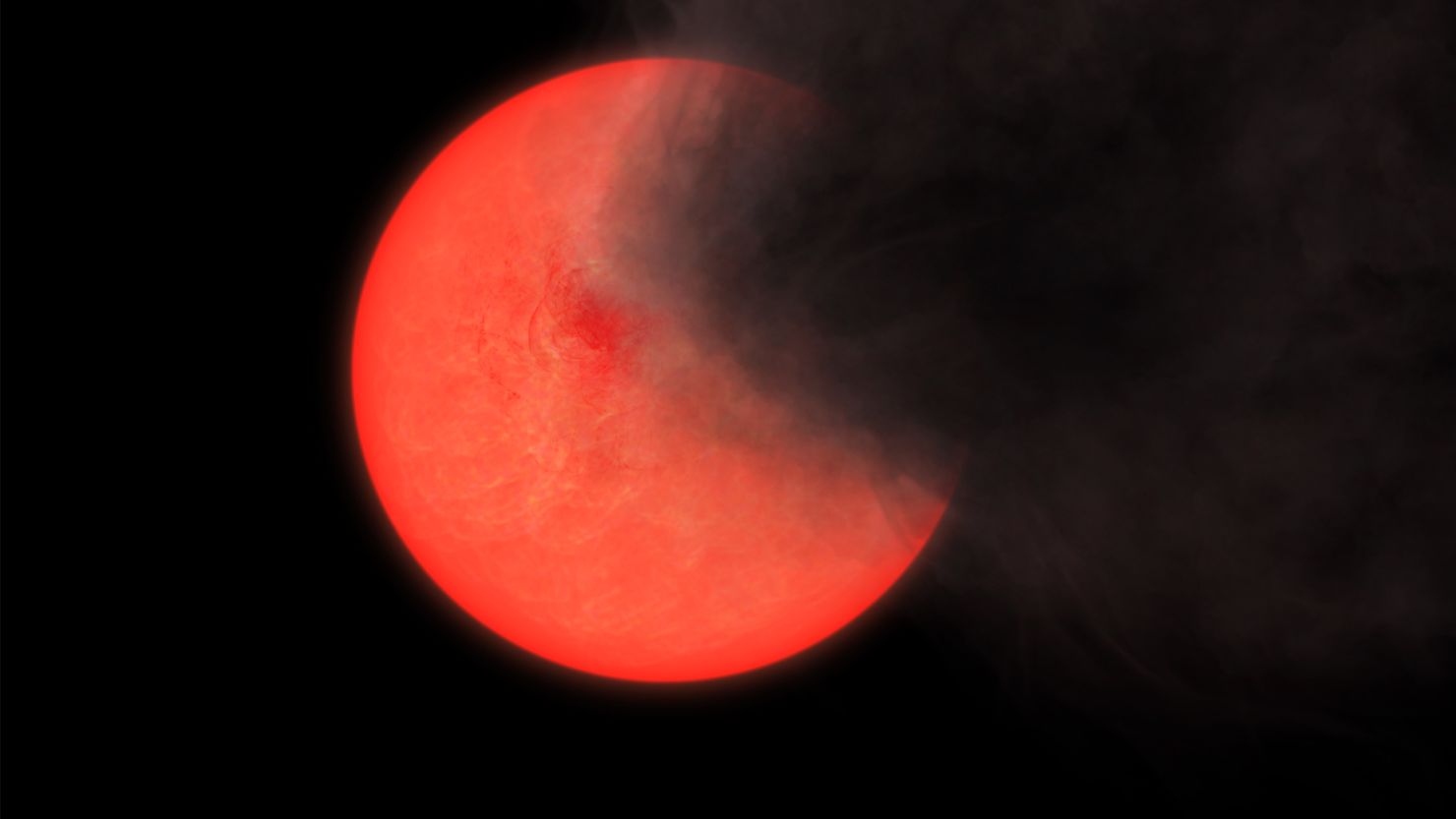

The bulge is the central group of stars that form the Milky Way. This represents a quarter of the whole galaxy and contains some of the oldest stars, reason why it has been object of study of many astronomers, since its characterization can reveal a lot of information about the history and evolution of our home in the Universe.

Nevertheless –in spite of the significance behind it– it has been difficult for the specialists to reveal its mysteries; given that we are inside the Milky Way we can only observe it partially, which is not the case for the rest of our neighbor galaxies.

Despite this problem, an international team of astronomers, led by the astronomer from ESO, Elena Valenti, and the researcher from the Millennium Institute of Astrophysics MAS, Manuela Zoccali, who is also part of the Astrophysics Institute of the Universidad Católica, managed for the first time to empirically measure the total mass of the bulge: 20,000 millions solar masses. This study is featured in the latest issue of the prestigious Astronomy & Astrophysics journal.

In order to carry out these measurements, this team used data from the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) survey –part of ESO and led by MAS researchers– plus data obtained from the Hubble Space Telescope.

“We empirically measure each of the stars that form the Milky Way bulge, from the faintest to the brightest ones. Thanks to the VVV’s excellent space resolution and its large field of observation, we could count all the stars in a stage of their evolution where they burn helium in their core. These are easy to see, and since they are bright, we hardly miss one. However, we also needed to identify the faintest ones. In a previous study –in which we studied a very small area reached by the space telescope– we had established the connection between the number of bright stars and the ones that are not and their total mass. Now, applying this same conversion to the number of helium-burning stars that we counted in the entire bulge using the VVV survey, we determined the total mass of the bulge, this important area of the galaxy,” explains Zoccali.

With all this information, the team came to the conclusion that this area of the Milky Way has a mass as if 20,000 millions of suns where contained there. In addition, the researcher remarks that they not only estimated the total mass of that area, but also the mass profile, that is, the density in this same area.

For this study, other complementary tools were used. For example, the reddening map, created by the Chilean astronomer Óscar González, currently working at University of Edinburgh, helped to avoid gas and dust blocking the lights from the stars.

According to the MAS researcher, the total mass of the bulge had been calculated before, but then the only possible way to do so was using a theoretical model to convert star’s light or speed into mass.

According to the astronomer, this discovery “helps us to place our galaxy in a more global context, allowing us to know the properties of our home. This is a number that will end up in textbooks about the galaxy, since this is an accurate number of the stars’ mass that form the bulge.”

In addition to Zoccali, Valenti and González, the team in charge of this discovery was formed by Enrico Marchetti and Marina Rejkuba, ESO researchers; Dante Minniti, MAS Deputy Director and Universidad Andrés Bello researcher; Javier Alonso – García from Universidad de Antofagasta; Maren Hempel from UC’s Astrophysics Institute and Alvio Renzini from Astronomical Observatory of Padova.

Link to this paper[:es]

A pesar de que existían mediciones anteriores, éstas utilizaban, además de observaciones, también algún modelo teórico. Por primera vez científicos del Instituto Milenio de Astrofísica MAS y del European Southerm Observatory ESO realizan una estimación totalmente empírica de la masa total de las estrellas que conforman el bulbo de la Vía Láctea.

El bulbo galáctico corresponde a la región central de estrellas que constituyen la Vía Láctea. Se trata del cuarto del total de toda la galaxia y además contiene algunas de sus estrellas más viejas, razón por la cual ha sido objeto de estudio de muchos astrónomos, ya que su caracterización nos puede revelar mucha información respecto a la historia y evolución de nuestro hogar en el Universo.

Sin embargo, a pesar de esta importancia, ha sido difícil para los especialistas develar sus misterios, ya que al encontrarnos dentro de la Vía Láctea sólo es posible observarla parcialmente, lo que no sucede con galaxias vecinas.

Pese a esta dificultad, un grupo internacional de astrónomos, liderados por la astrónoma de la ESO Elena Valenti y Manuela Zoccali, Investigadora Asociada del Instituto Milenio de Astrofísica, quien además es astrónoma del Instituto de Astrofísica de la Universidad Católica, lograron medir por primera vez de forma empírica la masa total del bulbo galáctico, cifrado en 20 mil millones de masas solares. La investigación aparece destacada en la edición más reciente de la prestigiosa revista Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Para realizar estas mediciones, el grupo utilizó datos del survey Vista Variables de la Vía Láctea (VVV) perteneciente a la ESO y liderado por investigadores del MAS, sumados a otros obtenidos con el uso del telescopio espacial Hubble.

“Lo que hicimos fue medir de forma empírica cada una de las estrellas que conforman el bulbo galáctico, desde las más débiles hasta las más luminosas. Gracias a la excelente resolución espacial y la gran área del cielo cubierta por el VVV, pudimos contar todas las estrellas en una fase de su evolución en la que queman helio en su núcleo. Éstas son fáciles de reconocer, y por ser luminosas, no perdemos casi ninguna. Sin embargo, necesitábamos también conocer las más débiles. En un estudio anterior en el que estudiamos una región muy pequeña correspondiente al campo de visión del telescopio espacial habíamos determinado la correspondencia entre el número de estrellas luminosas y las que no lo son y su masa total. Ahora aplicando esta misma conversión al número de estrellas que queman helio que contamos en todo el bulbo a través del VVV, determinamos la masa total del bulbo, esta importante zona de la galaxia”, explica Zoccali.

Con ello el equipo concluyó que esta zona de la Vía Láctea tiene una masa igual a si estuvieran contenidos ahí 20 mil millones de soles. Además la investigadora cuenta que no sólo se estimó la masa total de esta zona, sino que también el perfil de masa, es decir, cómo se distribuye la misma en esta área.

Para el estudio también se usaron otras herramientas complementarias, como un mapa de absorción estelar, creado por el astrónomo chileno Óscar González, actualmente en la Universidad de Edimburgo, que permitió sortear el gas y el polvo que bloquea la luz de las estrellas.

Según la investigadora del MAS, anteriormente se había calculado la masa total del bulbo de la galaxia, no obstante, sólo había sido posible medirla utilizando un modelo teórico para convertir la luz o la velocidad de las estrellas en masa.

Según la astrónoma este descubrimiento “Nos ayuda a colocar a nuestra galaxia en un contexto más global, conociendo las propiedades del lugar donde vivimos. Es un número que terminará en los libros de texto sobre la galaxia, pues se trata de una cifra certera y precisa de la masa de las estrellas que componen el bulbo”.

Además de Zoccali, Valenti y González, el equipo a cargo de este descubrimiento estuvo compuesto por los investigadores de la ESO Enrico Marchetti y Marina Rejkuba; Dante Minniti, subdirector del MAS e investigador de la Universidad Andrés Bello; Javier Alonso – García de la Universidad de Antofagasta, Maren Hempel, del Instituto de Astrofísica UC y Alvio Renzini del Observatorio Astronómico di Padova.

Lectura de Fotografía: La línea punteada marca la zona de la galaxia estudiada. Crédito: Stephane Guisard.

[:]